in Airline trends & analysis , Other , Aviation Banks and Lenders

Friday 5 April 2019

How are airlines coping with the MAX grounding?

UPDATE: Boeing announced on 5th April that 737 MAX production will be reduced from 52 to 42 airplanes per month starting in mid-April.

The preliminary report on the Ethiopian crash published this week makes for grim reading and raises questions on how quickly Boeing will be able to roll out fixes for the MAX.

Crash investigators highlight that the pilots were unable to manually override MCAS but were unable to explain why the angle-of-attack sensor provided fluctuating readings in the first place.

Airlines are clearly preparing for a lengthier grounding. Southwest Airlines, who operate the most MAXs at 34 aircraft, has removed the type from its flight schedules through May, extending an earlier timeline from 20th April, while United Airlines has not scheduled MAX flights until 5th June.

Ominously, recent developments in the MAX saga point at a lengthening of the grounding period. A preliminary report of the Ethiopian crash released on 4th April reveals that pilots followed instructions provided by Boeing last November, following the Lion Air crash, on how to deal with an inadvertent Manoeuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) triggering by faulty sensor data. Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg responded to the report saying it is the OEM’s responsibility “to eliminate this risk.”

Boeing has maintained a production output of 52 new MAXs per month as it continues to work on a software fix for the MAX’s MCAS (see Ishka’s earlier Insight). Further delays could result in hundreds of MAX deliveries being delayed for months.

Ishka examines the level of optimism hinted by other airline schedules, the impact of the immediate MAX order backlog on operators, and how large and small airlines exposed to the type are reacting.

Scheduling hints

Click here to download the data behind the chart.

Source: OAG Schedules Analyser

Click here to download the data behind the chart.

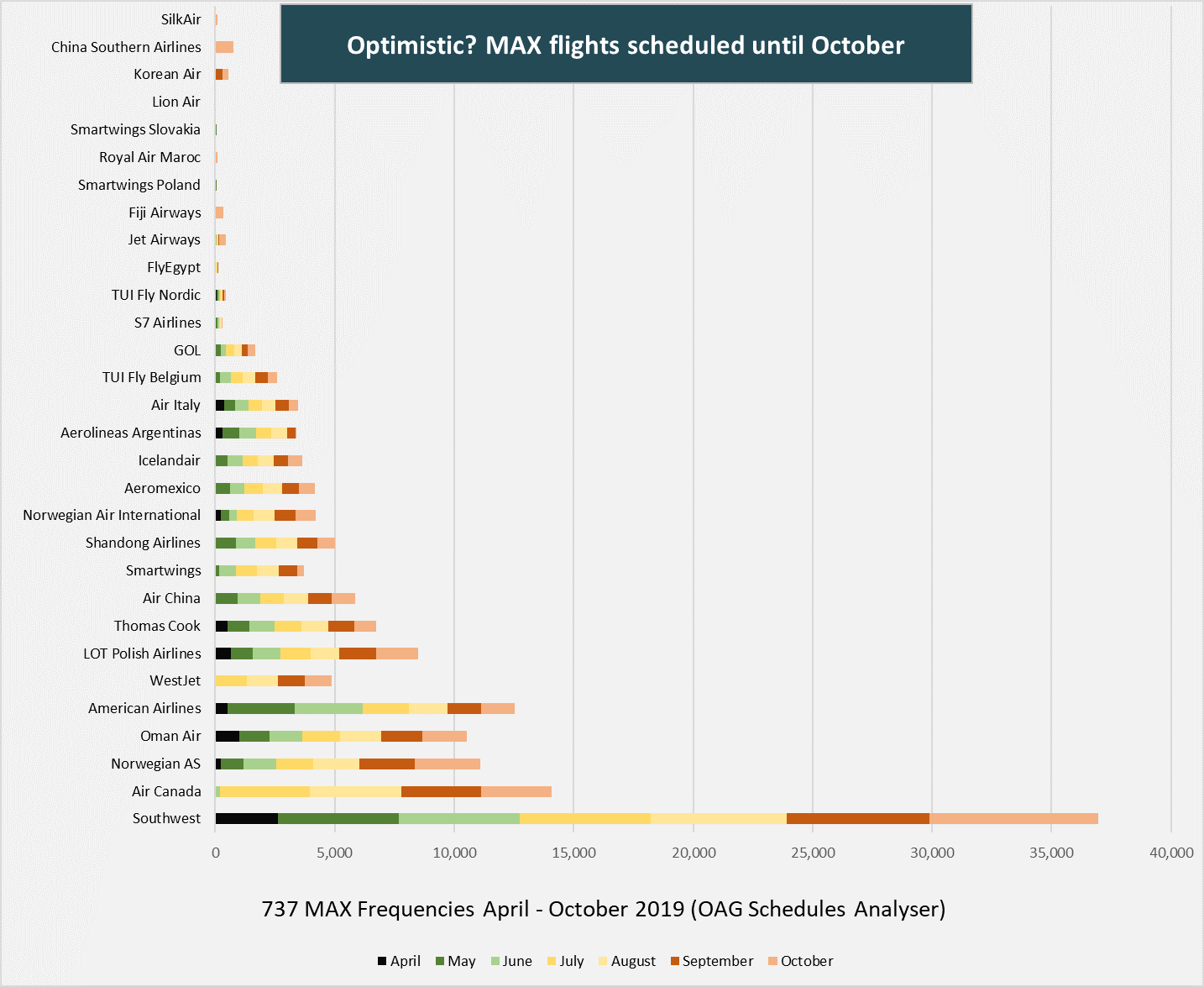

The above chart shows scheduled 737 MAX frequencies until October in the OAG database. Only data for 30 airlines could be retrieved, suggesting excluded MAX operators like United Airlines or Turkish Airlines are disregarding grounding forecasts (including their own) and abstaining from scheduling the type on public databases. Among the 30 airlines shown, some like Southwest or Oman Air show scheduled MAX flights for April despite these being operated by different equipment.

However, the chart gives some hints as to the level of optimism across operators for the MAX’s return to operation. Some carriers like Shandong Airlines, Icelandair, Aeromexico or Air China are still hoping to fly MAXs next month. Others like Air Canada and WestJet do not expect to operate the type until at least July, while China Southern Airlines, the world’s sixth largest operator of the MAX, has not scheduled flights until October.

The impact on smaller airlines

Click here to download the data behind the chart.

Source: CAPA Fleets and Ishka Research

Click here to download the data behind the chart.

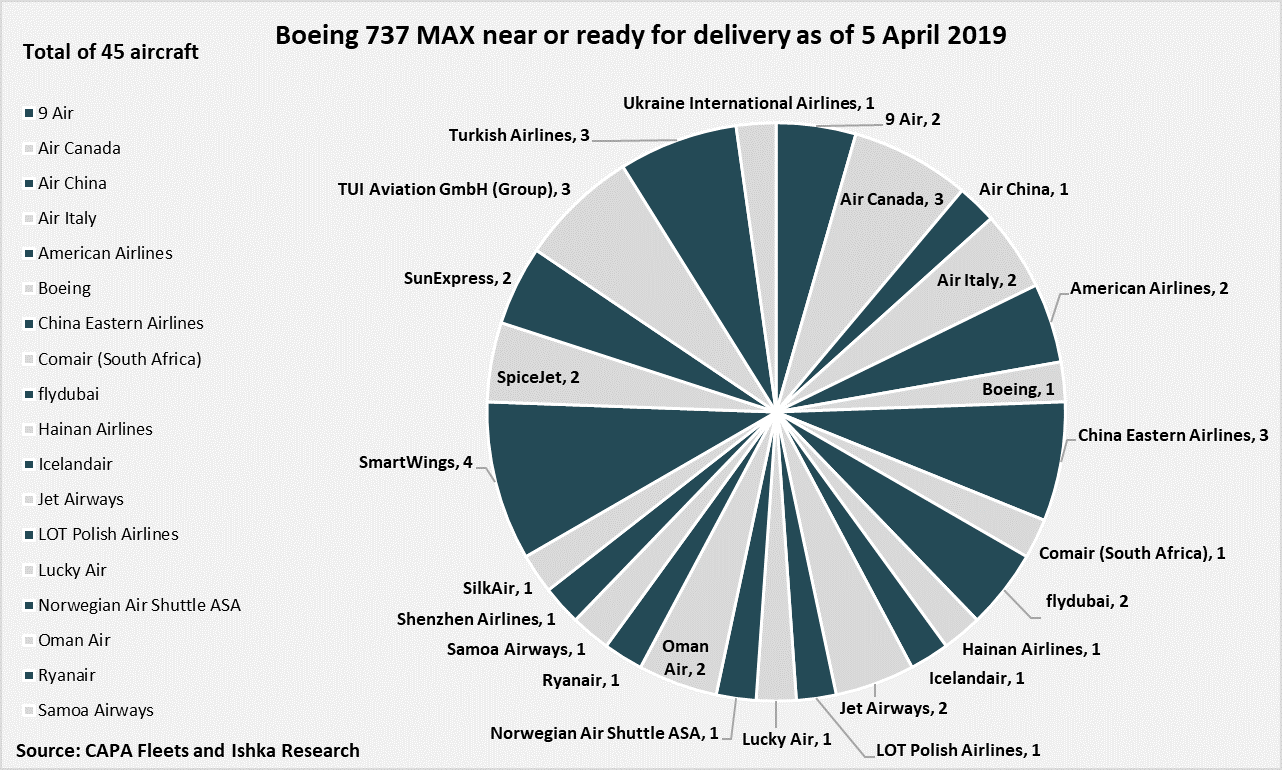

The chart above shows 45 end-of-production 737 MAXs which Ishka understands are ready for delivery or undergoing final checks and test flight. By some accounts, however, there could be up 60 aircraft worth $2.8 billion ready to be delivered. Of the 18 operators listed above, five are airlines with less than 40 aircraft in their fleet: 9 Air, Air Italy, Comair, Smartwings and Samoa Airways. Small carriers like these are unable to mitigate the MAX groundings and delivery delays with their existing fleets and are resorting to wet-leasing.

According to Flightradar24, Air Italy, a 14-aircraft airline with three operational MAXs and two more slated for delivery from April, appears to have wet-leased two Bulgaria Air aircraft: an A319 (MSN 3564) since 14th March, just two days after the EASA-mandated grounding, and an ERJ-190 (MSN 19000492) since 1st April. According to Romanian aviation news site Boardingpass.ro, the airline also leased a Blue Air Boeing 737-800 NG for the start of April. Air Italy has also scheduled its A330-200s on flights previously flown by the MAX to Dakar, Sharm el-Sheikh, Cairo, Accra and Lagos.

Comair, a South African all-737 airline of 21 aircraft operating for British Airways and its own brand Kulula, is continuing operations of two ad-hoc wet-leased aircraft since the end of last year to mitigate fleet maintenance backlog: an A320-200 (MSN 53) from Global Aviation Operations and a 737-300 (MSN 27346) from Star Air. Comair already has one MAX in its fleet and was expecting the second of a further nine to be delivered in Q1 of 2019.

Smartwings, a Czech all-737 airline with 11 MAXs in its fleet and expecting a further four in the immediate future, appears to have cancelled some flights and, according to Czech newspaper Zdopravy, it has agreed to wet-lease four Swift Air 737-800s. The first of these, MSN 32917, began operating on 21st March.

Samoa Airways, which was expecting to receive a brand-new 737 MAX 9 from Air Lease Corporation in March, has cancelled that lease and is negotiating the leasing of a Malindo 737-800 NG.

The airlines mentioned above are just four examples of small operators scrambling to cope with the unforeseen grounding of the MAX. Other smaller airlines moving to mitigate MAX groundings are Poland’s LOT Airlines, by wet leasing three 737-800 NGs from Slovakian airline GO2Sky and another two from Blue Air, and Icelandair, which will be leasing two 767s from April and May until September.

The impact on larger airlines

Major airlines expecting to operate MAXs or with a number in their fleets have been less affected by the groundings.

Air Canada is one such case. The airline had 24 737 MAX in service, or 6% of their total schedules, and had six due for delivery in March and April. The airline stated on 19th March that its MAXs will not return to service before 1st July and has adjusted operations to ensure 98% of its routes are covered.

Other Air Canada aircraft will substitute MAXs, leases due to end have been extended, and the arrival of used equipment has been accelerated, such as ex-WOW Air Airbus A321s (see Ishka’s earlier Insight). The airline has also contracted short term wet-leasing capacity from Air Transat for specific routes and temporarily cancelled routes with no suitable replacement aircraft, such as Halifax and St. Johns to London Heathrow. Some passengers have also been rerouted on other routes to increase utilisation of the operational fleet.

Oman Air, with a fleet of 55 aircraft of which 9% are MAXs, appears to be adopting a similar strategy to Air Canada. The airline has cancelled some services such as Muscat to Kuwait, reduced frequencies on some narrowbody routes by deploying widebodies, and increased utilisation of its Embraer ERJ-175 fleet by using them in routes previously flown by 737s. The airline was expecting the delivery of at least two more MAXs in the first half of the year.

The Ishka View

Airlines are digesting the findings of the preliminary report on the Ethiopian crash published this week and what this might mean for their operations. As mentioned earlier, crash investigators highlight that the pilots were unable to manually override MCAS, but investigators are still unable to explain why the angle-of-attack sensor provided fluctuating readings in the first place. A convincing fix to the former and an answer to the latter will be needed for the MAX to fly again, hinting at a lengthier grounding.

The cost for Boeing will, of course, only escalate as the grounding persists. The OEM has halted MAX deliveries but continues producing over 50 units per month, meaning increasing storage costs. Airlines are also positioning themselves for negotiation by publicly voicing thoughts around cancelling (or more likely deferring) orders for the MAX. Both SpiceJet and Norwegian have gone public with their plans to seek compensation from Boeing for costs incurred from the MAX groundings (see Ishka’s earlier Insight).

The economic cycle which pays for the aircraft (the airline revenues that paid for the lease rentals, which in turn paid the interest on loans or finance structures) has been disrupted by adding to the operating costs, and while compensations will be sought, they are unlikely to provide 100% coverage (see Ishka’s earlier Insight). The airline credit risk therefore comes strongly back into focus and vulnerable airlines have become another notch more vulnerable.

Sign in to post a comment. If you don't have an account register here.