UPDATE: This report was updated at 15:00 GMT on 9th February 2023 with a response from the Norwegian Environmental Agency and a link to its Climate Quota Regulation (Klimakvoteforskriften).

2nd UPDATE: An article published on 25th April 2023 by law firm Watson Farley & Williams (WFW) concludes that fears of liens being imposed on leased aircraft are “ultimately unwarranted” as minimal risk exists from a local law perspective. WFW’s article includes clarification on the enforcement mechanisms of the relevant schemes for the UK, Switzerland, and each EU ETS State (excluding Liechtenstein) from its network and correspondent counsel.

Norwegian low-cost carrier Flyr filed for bankruptcy and ceased trading on 1st February after an “unsuccessful” new financial plan and determining it had no alternatives for further operation. Having only launched operations in Summer 2021 amid pandemic headwinds, Flyr had a short existence but one with valuable lessons on the impacts of EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) obligations on airlines and, potentially, lessors.

Flyr’s bankruptcy was precipitated by a failed last-ditch attempt to raise NOK 330 million ($32 million) to pay for EU ETS quotas due in April 2023. Other recent capital raises and a wet lease agreement to redeploy half of its fleet (both central to its survival) were also contingent on the airline raising that NOK 330 million at the end of January.

For lessors, Flyr’s failure could mean more than just an aircraft remarketing task. Under EU directive 2008-101-EC, aircraft owners are liable for unpaid EU ETS quotas related to their aircraft when the operator cannot be identified (implemented in Norway via Section 1-3 of the Climate Quota Regulation or Klimakvoteforskriften). A PACE estimate reveals that Flyr has a potential fleet lien exposure of up to €33.6 million ($36.1 million) including a €100 per tonne of CO2 penalty in case of non-compliance – a figure in the ballpark of the failed January 2023 private placement that befell the carrier.

One legal source with knowledge of Flyr’s situation says they are “not aware” of Norwegian legislation providing Norwegian authorities with the right to detain an aircraft for unpaid EU ETS fees, but Ishka understands there are instances in European national legislation where this can be the case or – at the very least – where it can create legal quandaries for lessors.

Flyr’s demise has EU ETS at its centre

Flyr’s bankruptcy follows a deteriorating operational environment and snowballing financial difficulties. In October 2022, the airline announced steps to reduce cash burn (including furloughs and route cuts) amid decreasing discretionary consumer spending due to high inflation, interest rates, and energy prices. In November, the loss-making carrier said it had secured funds to survive the winter season, but it was only able to raise about half of the NOK 530 million ($50.73 million at the time) cash required via a private placement of shares.

At the same time, that insufficient first-stage November private placement became “dependent on raising further capital” by the end of Q1 2023 needed to pay “for the EU ETS quotas in April 2023” and to “ramp up” for the coming Spring and Summer. However, hopes for a subsequent capital raise dimmed after Flyr’s share price collapsed (trading at €0 since mid-November). An agreement to wet lease half of its fleet from March 2023 to another carrier was also contingent on the airline securing further financing.

Two days after warning it was facing “a critical short-term liquidity situation,” the Oslo District Court opened the bankruptcy of the airline on 1st February with attorney Stine D. Snertingdalen from Kvale Law Firm appointed as the receiver. According to the bankruptcy petition, the company had a little less than NOK 2.5 billion ($243 million) in booked debt and over 400 employees whose wage claims reportedly exceed NOK 30 million ($2.9 million).

A partner at the receiver law firm Kvale Law, Helge Østvold, told Norwegian news site E24 on 2nd February that it was working with aircraft leasing companies to accelerate the return of aircraft. Østvold noted that deposits totalling NOK 38 million ($3.7 million) had been paid by Flyr for the lease of aircraft including four aircraft that were yet to be delivered (a Flyr January 2022 prospectus suggests those four aircraft may be additional Boeing 737 MAX 8 due for delivery in 2023 from Air Lease Corporation).

Flyr’s fleet: All-leased Boeing 737 NGs and MAXs

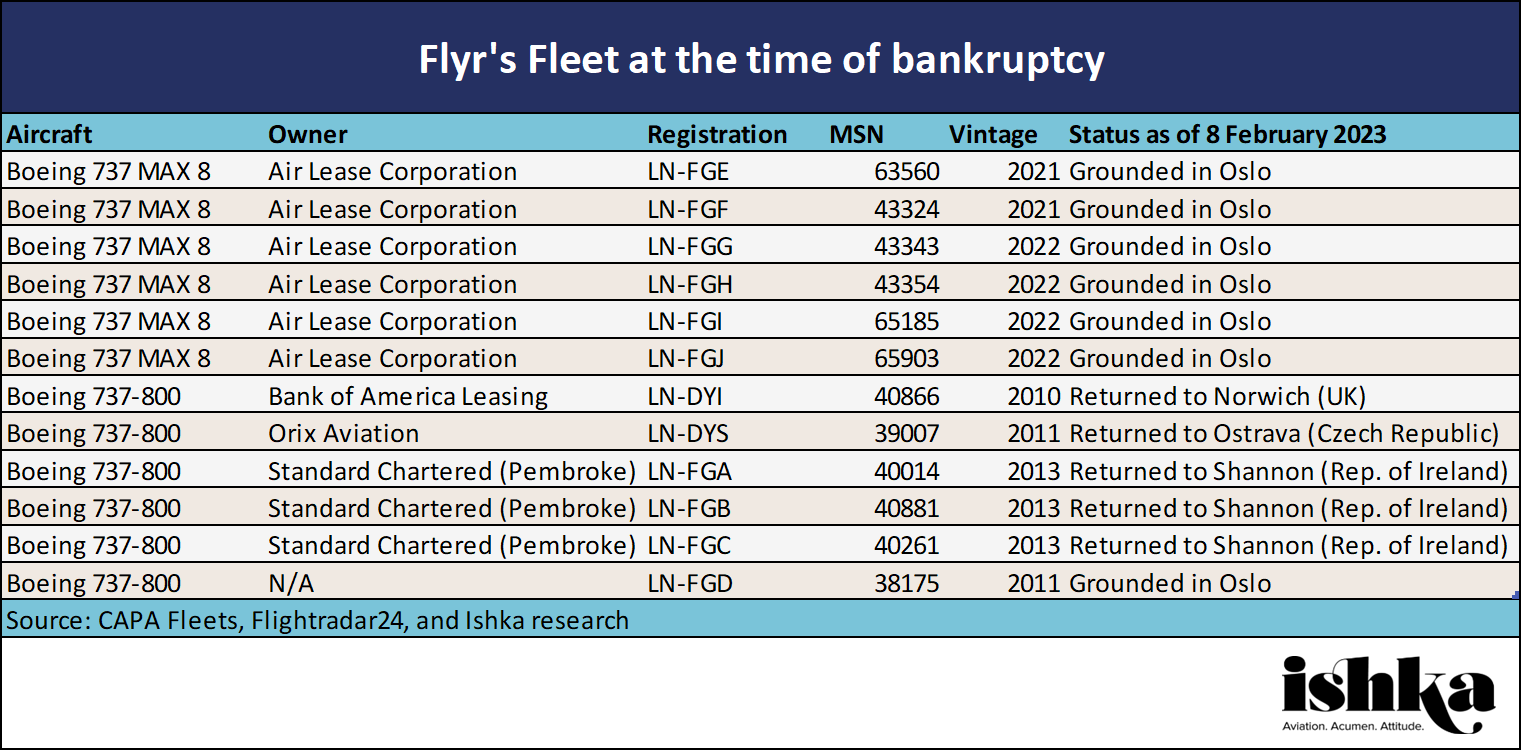

At the time of filing, Flyr had a fleet of 12 Boeing 737 aircraft (six 737-800 NGs and six 737 MAX 8s). All six MAX 8s were leased from ALC, with the 737-800 NGs leased from four other leasing entities which as per the same January 2022 prospectus and CAPA Fleets data include Standard Chartered Bank, Bank of America Leasing Corporation, and ORIX group. Total leasing liabilities for four used 737-800s aircraft as of 30th September 2021 were NOK 350 million ($34.1 million).

All five lessors exposed to Flyr are reportedly being represented by Ingar Fuglevåg, the head of aviation at Norwegian law firm Simonsen Vogt Wiig. Fuglevåg told E24 late last week that all parties were cooperating in facilitating the return of aircraft to the lessors. According to Flightradar24, a number of these aircraft were flown to Ireland, the UK, and the Czech Republic in the past few days.

The six MAXs, all leased from ALC, are reportedly headed for rival Norwegian Air Shuttle. On 6th February 2023 Norwegian confirmed in a filing to the Oslo Stock Exchange that it had signed a Letter of Intent (LOI) with ALC to lease six Boeing 737 MAX 8 in addition to three other 737 MAX 8 aircraft which Norwegian previously agreed to lease from ALC.

Norway-based airline analyst Hans Jørgen Elnæs said on Twitter that the additional MAX aircraft are the ex-Flyr aircraft. According to Norwegian, the aircraft would be delivered “in short time” ahead of the Summer 2023 season and a final agreement is subject to “certain closing conditions.”

PACE estimates €33m in potential lessor liabilities

Under UK ETS and EU ETS schemes (the latter also includes Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway), non-compliance by aircraft operators may create a contingent fleet lien liability on aircraft owners in a similar way as outstanding Eurocontrol charges. If Flyr fails to pay for its quota of EU ETS allowance for the previous year by the end of April 2023, there is a mandatory penalty based on the price that should have been surrendered plus €100 ($107) per tonne penalty on top.

Using the ETS function in the PACE calculator, the potential fleet lien exposure (including non-compliance fines) of Flyr’s fleet of aircraft under the EU ETS and UK ETS using an EU ETS Emission Unit Allowance (EUA) price of €85 per tonne is approximately €33.3 million ($35.7 million) – a figure in the ballpark of what Flyr was trying to raise at the end of January to cover its EU ETS obligations. The current price of EUAs is just under €100 per tonne, increasing that exposure to over €36 million ($38.6 million).

“The Norwegian regulator may have a similar right to the UK of seizure and detention of aircraft until EU ETS liens have been cleared. The UK’s rights of seizure, detention, and sale of aircraft resulting from ETS non-compliance are clearly stated in UK’s Climate Change Act – Greenhouse Gas Emissions Trading Scheme Regulations 2012. This is something that aircraft lessors, investors, owners, and financiers should be very concerned about,” Barry Moss, President of PACE ESG and Managing Director of aviation ESG risk advisory group AVOCET tells Ishka.

A legal source with knowledge of Flyr’s situation told Ishka that they were currently “not aware” of any Norwegian legislation that provides the regulator with any right of detaining an aircraft for unpaid EU ETS fees, nor did they believe was “any risk of lien or detention levied against any of the aircraft remaining in Norway.” The Norwegian Environmental Agency (Miljødirektoratet) told Ishka on 9th February that it was unable to answer questions related to EU ETS and Flyr given that Flyr's bankruptcy proceedings remain "in an initial phase."

The Ishka View

Flyr’s bankruptcy proceedings will shed more light on the causes that befell the carrier and any liabilities for creditors, but from details emerging it is increasingly apparent that the EU ETS played a key role in the carrier’s demise. New airlines in Europe such as Flyr are at a competitive disadvantage versus long-established carriers who, unlike new airlines, can benefit from free emission allowance allocations under the EU ETS. Since late 2020 and due to a variety of factors the price of EU ETS allowance has more than tripled, creating an even larger disadvantage for new entrants. As of 7th February EU allowances (EUA) were trading at €93 ($100) per tonne, compared to €20 to €30 before 2021. New operators who may no longer benefit from the New Entrants Reserve (NER) of free allowances, as may have potentially been Flyr’s case, are at a particular disadvantage.

EUAs are expected to average €81.4 a tonne in 2023 and €94.14 in 2024, a recent Reuters survey of six analysts showed, with average prices rising in 2025 to €102.24 euros/tonne. This is expected to increase financial pressure on European carriers and create an unfavourable environment for new entrants until the complete phase out free allowances for the aviation sector (which largely benefit established airlines) by 2026 (see ESG Extra: ‘EU agrees ETS reform but SAF rules slip into 2023’). This creates an airline credit concern for lessors exposed to airlines with weak financials, particularly new airlines that do not have access to historic free carbon allowances.