Wednesday 19 October 2016

Has the A340 programme delivered in terms of residual values?

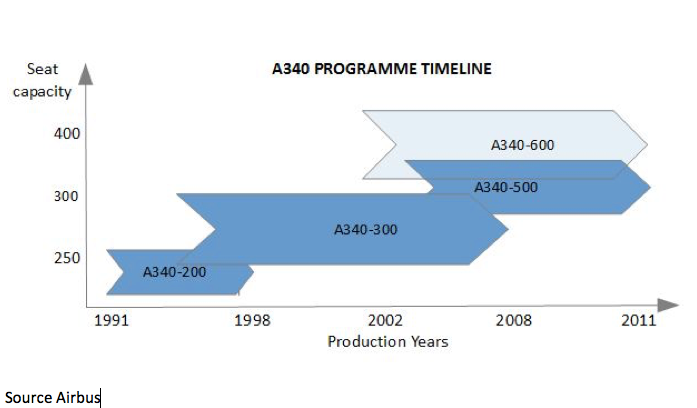

The Airbus A340 programme is now 25 years old, having first flown on October 21st, 1991. In total 377 units of the four-engined long haul aircraft were built over a 20 year period between 1991 and 2011, of which 290 remain in service. It’s sister programme, the twin-engined A330 family has fared much better, having sold upwards of 1,600 units and is still in production with 1,300 already delivered and a new version entering service in 2017.

Operators originally invested in an asset that would allow them to develop their long-haul networks more competitively than other aircraft available at the time. Despite competing successfully against the three-engined MD-11, and playing an important role for many carriers in terms of route expansion, the A340 soon faced competition from new twin-engine aircraft such as the Boeing 777. The dramatic increases in fuel costs during the 2000s led to the type falling out of favour with many operators and the order backlog dried up fast, even after new upgraded models were introduced. The latest wave of replacement, facilitated by the introduction of the latest generation of twin-engine long-haul aircraft (Boeing 787 and Airbus A350) has added further pressure on the marketability and therefore values of the A340 and other aircraft from the same generation.

The Ishka view is that the depreciation profile for the A340 reflects both the limited volume of sales achieved and the challenge of remarketability, when compared with other widebody programmes. Depreciation has consequently been steeper for the type than for other more popular types with similar mission capabilities in the same age category. Nonetheless, some carriers are benefiting from the range/seat-capacity mix offered by the type in specific missions, allied to attractive rental terms. The historical performance in terms of value retention now provides an opportunity for new customers and markets to develop.

Ishka analyses the current state of the A340 programme, its prospects in the secondary market and potential for value retention.

The rationale behind the A340 programme

Airbus based the A340 on the A300 fuselage and included fly-by-wire and other technologies developed for the A320 family. The A340 pioneered innovations when it was launched, making it a better economic proposition on many missions that were the preserve of the Boeing 747 classic, and with better performance figures than the three-engine MD-11, it made inroads into that market too. Singapore airlines switched to the A340 platform to launch new non-stop longhaul missions, having cancelled a corresponding order with McDonnell Douglas for MD-11s in 1991. The A340 programme was developed in tandem with the twin-engine A330 which helped Airbus spread R&D investment and keep costs down.

The first iteration of the family, the A340-300 became a direct competitor of the Boeing 777-200ER and later of its own sibling the A330-300. The A340-600 stretched version was introduced in 2002 to compete with the upcoming Boeing 777-300ER. Despite Airbus having first-mover advantage, the twin-engined Boeing 777 gained a larger market share in both instances, as higher fuel costs began to favour the efficiency of twin engine operations. These factors combined impacted market values for both the A340-300 and A340-600 variants in the long -term.

A340’s operational history

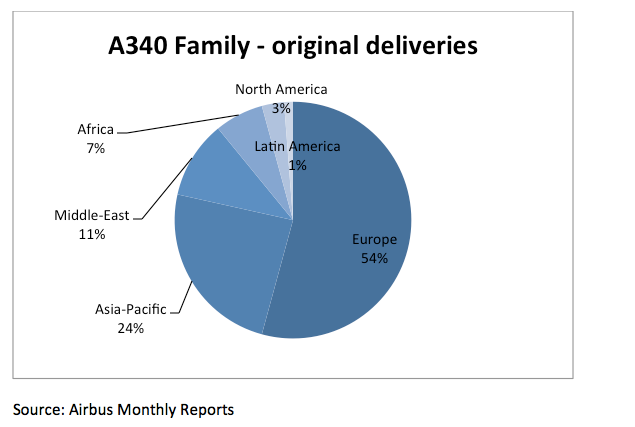

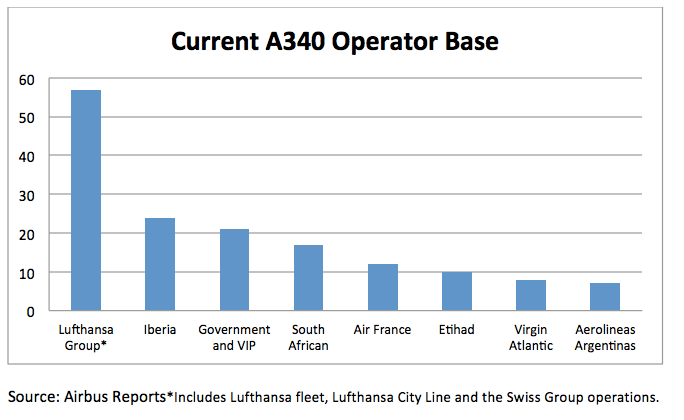

Lufthansa was the A340 launch customer and remains the largest operator of the A340 family. Initial sales for the A340 programme did not achieve a balanced geographical spread. Europe and Asia-Pacific received almost 80% of all deliveries.

The only A340 operator in North America was Air Canada; the carrier ordered eight A340-300 for its widebody fleet and two A340-500 for ultra-long haul services to Hong-Kong. Similarly, the A340 sold in thin numbers in Africa and Latin-America whilst small numbers of the fleet were delivered to the Gulf Carriers. Liquidity of the type was also impaired by this factor. Iberia and Lufthansa still account for a significant share of the operating fleet. Remarketability of the aircraft was affected by a small operator base and fleet concentration, as summarised in the following chart:

Lufthansa mainline operates 24 A340-600 aircraft and 18 A340-300 aircraft; some of the A340-300 aircraft are now operated in high density routes from Frankfurt by its subsidiary Cityline. Lufthansa Group owned Swiss Air operates 10 A340-300 and is in the process of transferring four of them to its Edelweiss Air unit to be deployed on leisure routes in South East Asia and Hawaii. The second largest operator is Iberia. The carrier is in the process of retiring all of its A340-300s and is upgrading its A340-600 fleet; the carrier will keep the A340-600 to operate trunk routes and payload restricted destinations in Latin America.

Bearing in mind the limited secondary market size, one underlying trend has been for some first tier airlines to deploy their A340s in secondary roles within their networks. Lufthansa and Iberia are two such operators and should by now be benefitting from much reduced ownership costs. In the current, relatively low-fuel price environment, it can make economic sense for these carriers to retain the aircraft in specific roles or for specific routes.

Carriers with less extensive networks like Virgin Atlantic have chosen to replace all their A340 variants with twin-engine aircraft. The size of the A340 fleet has reduced most significantly in Asia-Pacific. Early operator Singapore Airlines has now retired all of its A340-300 and A340-500 aircraft; Cathay Pacific has retired more than half of its A340-300 fleet which now stands at only five aircraft. China Airlines, China Eastern and Thai Airways have now retired all their A340-600 aircraft.

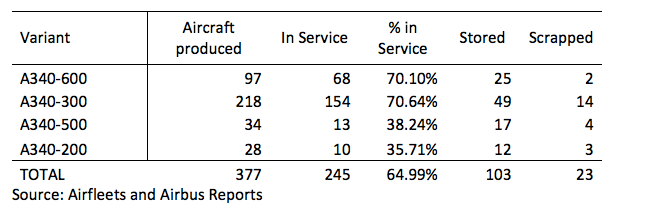

Some A340 family aircraft have transitioned to the VIP/Government sector. Second tier airlines like Aerolineas Argentinas, HiFly and Iran's Mahan Airlines have acquired used aircraft. Despite the weakness in the secondary market for the A340 family, nearly 100 transactions were recorded against the type in 2014 and 2015, including lease extensions, new leases, and purchases for both operating and part out. Commonality with the A330 will also provide part out and support potential. The table below summarizes the current survival rate for the type.

Of all the A340 aircraft delivered, around 65% are still in active service. This figure was exacerbated by the early retirement of the A340-500 ultra-long-haul variant. There are at least 11 A340-500 listed for sale, eight of which are ex-Emirates aircraft. In comparison more than 80% of the Boeing 777-200 and A330 fleets are still in active service. The early retirement rate reflects the lack of an extensive secondary market and has had a bearing on A340 aircraft current market values.

The operator base has not changed significantly since deliveries peaked in 2005. Lessors did not buy into the programme in large numbers. The former ILFC was the only lessor that placed significant orders for the type (16 A340-300 and 13 A340-600 aircraft) and in 2013 took a $1.2 billion noncash impairment and reduced the holding periods for their A340 fleet below the original 25-year projection.

No freighter conversion

Aircraft residual value retention can benefit from an extended life in the air cargo market. A paradigm in the aircraft market used to be that when an aircraft types’ value declined to a point where it could be acquired for conversion at a price that would justify the investment for conversion, then enough models of such type could be converted to cargo roles. However the cargo market dynamics have also changed to such an extent, that a growing proportion of the world's cargo is now carried as a bypass product of passenger operations, as belly cargo. There is currently weak demand for dedicated widebody converted cargo aircraft; where there is a need for conversions today, the market is focused on narrowbodies and some twin-engine widebody types. While cargo conversion programmes have been offered for the A340-300, the length of the A340-600 fuselage might cause centre-of-gravity issues as a pure freighter.

A340 value performance

Market values of the A340 family have depreciated more rapidly than for many other widebody aircraft families. Some estimates suggest that ‘half-life’ current market values for the A340-300 will today range from around US$5.0 million for the oldest examples(1992-vintage) to aroundUS$20.00 million for younger aircraft (2008-vintage). The oldest aircraft (over 23 years of age) would today, in market value terms, be worth between 5% and 21% of its delivery value, with the variation reflecting ‘half-life’ to ‘full life’ maintenance status, whilst the youngest A340-300, now 8 years old, would today be worth between 21% and 36% of its delivery value, on the same terms.

A 16 year old A340-300 would today be worth between 7% and 21% of its original value. In comparison, a 15 year old Boeing 747-400 would command between 8% and 26% and a 777-200ER would command between 15% and 31% on the same terms. The A340s sistership, the A330-300, has fared much better, commanding between 27% and 44% of its delivery value after 16 years, depending on maintenance status (‘half-life’ to ‘full-life’).

The market values for the A340-600 have also experienced a steep depreciation behaviour, although not as aggressively for the older models, which are estimated to be worth between 19% and 43% of their delivery value, with the variation reflecting ‘half-life’ to ‘full life’ maintenance status. Values of the -600 variant have stabilised and is currently concentrated around the US$25 million mark for all vintages assuming ‘half-life’ status. Oriel reports that market values for the aircraft range from US$21 million for a 2001-build airframe to US$25.25 million for a 2010-build. The maintenance condition of the aircraft is even more relevant in understanding the value dynamics of the A340-600, as ‘full life’ status of such aircraft could theoretically double their value (a widebody airframe, with four large engines can generate significant maintenance related costs).

As the values for A340-600s have converged, aircraft age is unlikely to resurface as a value differentiator in the future unless fuel prices decline significantly. Most of the ‘value’ of the aircraft will be in their engines and maintenance condition. The transfer to VIP/private operation, niche and opportunistic operators and/or more part-outs are a likely scenario once mainline carriers start retiring their fleets.

Values for the ultra long range A340-500 also demonstrate an aggressive depreciation profile. The total fleet delivered was small and most of the original operators have retired the type from mainline operations. Around half of the fleet is now available for sale and/or is parked. Oriel reports that values for the type, regardless of vintage, are around US$18 to 20 million. Consequently, an older A340-500 (2003 vintage, i.e. 13 years of age) is currently considered to be valued at 17% to 42% of its delivery value, whilst the youngest A340-500s (2010 vintage, 6 years old) is expected to trade at 21% to 49% of its delivery value, with the variation reflecting ‘half-life’ to ‘full life’ maintenance condition.

Emirates was the largest operator of the A340-500, which allowed the carrier to gain early access to city pairs in North-America but the aircraft was quickly superseded on their network. Without a tangible secondary market the A340-500 has been significantly impacted in residual value terms. Oriel’s forecasts indicate that by the end of this decade the variant could be trading at values reflecting less than 10% of the original delivery value. The ultra-long-haul market did not live up to early expectations with Boeing also delivering limited numbers of its B777-200LR product, but in contrast with the A340-500, the Boeing product has not witnessed the same degree of retirements by operators, although values for that type have also been impacted. Both manufacturers are venturing back into the ultra long haul space with new models.

The Ishka View

After 25 years of service, 65% of the A340 fleet variants remains active but the pace of frontline retirements is likely to accelerate. Even in a low-fuel environment, the maintenance burden associated with four engines is a considerable issue for operators; this is even more critical for the A340-600 Rolls-Royce powered aircraft. We expect to see more fleet transfers to second tier airlines, and support programmes from both owners and the airframe/engine OEMs to improve the economics of operating the A340. Large operators like Lufthansa will keep redeploying the aircraft in selected routes where it makes economic sense and routes where four-engine performance is desired.

The type may not have delivered in terms of residual values but it has played an important role in developing long-haul markets. The A340 was designed as an ‘ETOPS immune’ aircraft at a time when oil prices were low. The long-haul market has evolved since the early 1990s, and fuel price has been volatile to an extent that could not have been imagined at the time. This evolution has had an impact on other comparable types as well. In the medium term there will also be a wave of Boeing 777-200ER retirements. This will generate further market pressures for the values of both types, but also new opportunities to fly these aircraft by operators attracted to their lower acquisition or rental costs.

The A340s value retention has further highlighted the underperformance of widebodies in general. It is not the only widebody model that is failing to live up to initial expectations. Ishka will be looking at this in more detail in future articles.

Sign in to post a comment. If you don't have an account register here.